Once in a lifetime, if you’re lucky enough, you manage to finish reading a book that’d make you wish you had read it sooner.

For me, it was One Hundred Years of Solitude.

I had begun reading the book as soon as Amazon delivered it to me — about two years ago. Then we had a falling out. I read through about sixty pages before I realised it was too complex and too “out there” for my intellect. I felt intimidated. I couldn’t understand why I couldn’t understand the narrative. Maybe it was the fine print and the font that I didn’t admire, I told myself.

Thinking I’d read it later, I cast the book aside waiting for motivation to strike me hard enough to pick it up again. Some time that time, a friend wanted a book. I suggested One Hundred Years of Solitude, but I also warned her that it had given me a block. She took it nevertheless.

That was the last I saw the book until last month, almost a year and half later.

One cold morning a line from the story popped into my mind: “Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.” Even though the book had thrown me off, that queer line had stayed with me. That’s when I realised I should give the book another chance. I got the book back from my friend and dove in right away.

It took me a good one week to finish the book. I whizzed through over half of the story, slowing down as the narrative progressed. Many times, I went back two pages to make sure I followed which Aureliano did what. I had to scan the family tree hundreds of times before I understood who’s child Amarantha was and who her child was.

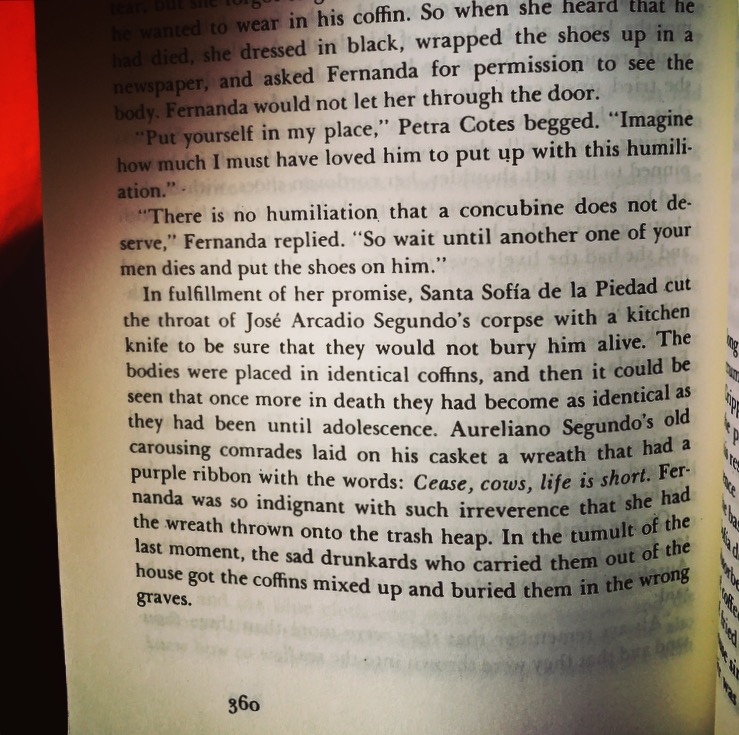

I speed-read some parts while I cherished other parts of the story. I stopped at beautiful turns of phrases, and gawked at clever word choices. And then I paused and took pictures when I saw words of wonderment.

When I did finish reading it, however, I wanted to kick myself. I chided myself for missing out on so much pleasure the first time I tried reading it. If only I had tried harder to endure the initial confusion, I would’ve enjoyed a glorious read much sooner.

Perhaps it was meant to be. Perhaps I couldn’t read it then because I wasn’t mature enough. Maybe now was the time I needed it the most. Just like the Buendía family had waited a hundred years to decode the prediction of their fortunes and misfortunes, I had let history repeat itself before decoding the joys of One Hundred Years of Solitude.

You should read this book, if you haven’t already. If you have, however, tell me, what was your initial reaction?