Volunteering is the best way to experience a new society, right?

So when the Multicultural Festival came around, I signed up as a general volunteer—you know, the ones wearing a red festival t-shirt and a hat, and a lanyard too large for their body—wandering around the perimeter smiling at those gorging on meat on a stick, sipping their beer before stepping away so that it doesn’t spill over before they reach their friends.

The festival started at 4 pm last Friday, with cultural performances and food stalls all the way through 11 pm. When I showed up at 4, a half hour earlier than the start of my shift, the place thronged with a hum of excitement. The sun sprawled on us as volunteers scattered throughout the city circle, taking their positions, armed with brochures, information packs, while the area wardens double-checked their walkie talkies, strapped on and ready to go.

The moment I stepped out into the festival ground, I regretted not carrying my water bottle. The festival organisers had done a tremendous job of setting up water filling stations every few metres, but without my bottle, I didn’t stand a chance. When at last I gave up my ego and picked up a plastic water bottle, drained and desperate, I promised never to do that again.

It didn’t take me too long to study the festival map. Six stages with three or four tents that accommodated smaller performances, spread across five major streets in the city centre. I’d walked around that part of city enough of times to know what lay where, and after two complete rounds, I’d memorised the locations of each stage.

Equipped with so much information, I began wandering. For that was my role as a general volunteer. I was to walk around with a welcoming smile, answering questions, and helping out anyone in distress. It had all seemed easy and fun on paper. And yet as I walked around I felt myself suffocating under the smoke of charred meat, barbecue and grilled citrus waffling throughout the streets, mingled with the joyous cries of lolly-sucking kids and the satisfied lip-smacking of bratwurst-wolfing adults.

On my right, noodles were sizzling, fried with eggs and chicken. From the left came yells advertising crepes—savoury and sweet—French, with gluten-free and vegan options. Baos, or steamed buns, weren’t too far away, sitting right next to the street food extravaganza of masala dosa and curry. A little further were Croatian beers, Sydney ice-cream, Ethiopian lentils and beef stews with flavoured injera.

Row after row showcased food from all over the world, in various shapes and sizes—from pulled pork burgers to the so-called healthy zucchini fritters, from paella to pan-friend momos, from fresh-squeezed orange juice to vodka-infused lemonade.

Overwhelming is an understatement. For five hours, I let the crowds push me from one place to another, as I tried to find my way through, only wanting to return to my starting point. As I left the festival that evening—four hours before the performances ended for the day—I was ready to hit the bed and not return for my shift the next day. I didn’t want to volunteer ever again.

But on Saturday afternoon, I arrived again, signed in to my shift three hours early, and started patrolling the grounds, looking for something more engaging than dead meat. Fortunately, that second day was the best.

In most cultural events that are advertised on Facebook with flyers abound and hashtags galore, people throng in thousands, flashing cameras at dancers as if they’d never before seen a blend of colours or beaded jewellery. Our impression of culture is often so stereotypical that we can’t imagine anything beyond a stage performance featuring slender female dancers and flavoured meat.

However, this multicultural festival tried to showcase some genuine culture. Not only did it feature music and food from various countries, but it also accommodated embassies of various nations. Why, one of the most popular aspect of the event—aside from the German beer and sausages—was the EU village. For an entire day, a large section of the festival hosted embassy stalls where delegates and foreign representatives shared brochures, travel advice, traditional information, and snacks. They even gave away free EU passports at the European Union tent—a fun activity for the young and the older where you could walk your way through all the tents of the EU countries and get your passport stamped at each tent.

A little later that day came the iconic Multicultural Festival Parade. As the name suggests, it’s a tremendous walking and dancing display of culture by the many countries that call Canberra (and Australia) home. From indigenous musical representatives to Chinese dragon dance, to Korean music, south Indian drumming, Bulgarian dancing, Brasilian samba, belly dancing, and more, the entire parade was a blurry flourish of colour.

Each of the six main stages represented a region. For instance, stage five was for African and Pacific Islander performances, food, and crafts, whereas stage two and its surrounds featured Celtic performances and Scottish traditional foods, information, and dance troupes.

Day two was more satisfying than the first one.

When I woke up on Sunday, hoping to make it on time to hear some multi-lingual poetry at 10 am, I realised I’d been stressing myself out. I had to lie in bed until I had to leave. My shift was to start at 1pm and I checked in 10 minutes prior.

Having spent two whole days at the festival without staying anywhere long enough to enjoy any performance completely, I’d decided to let it all go and have fun.

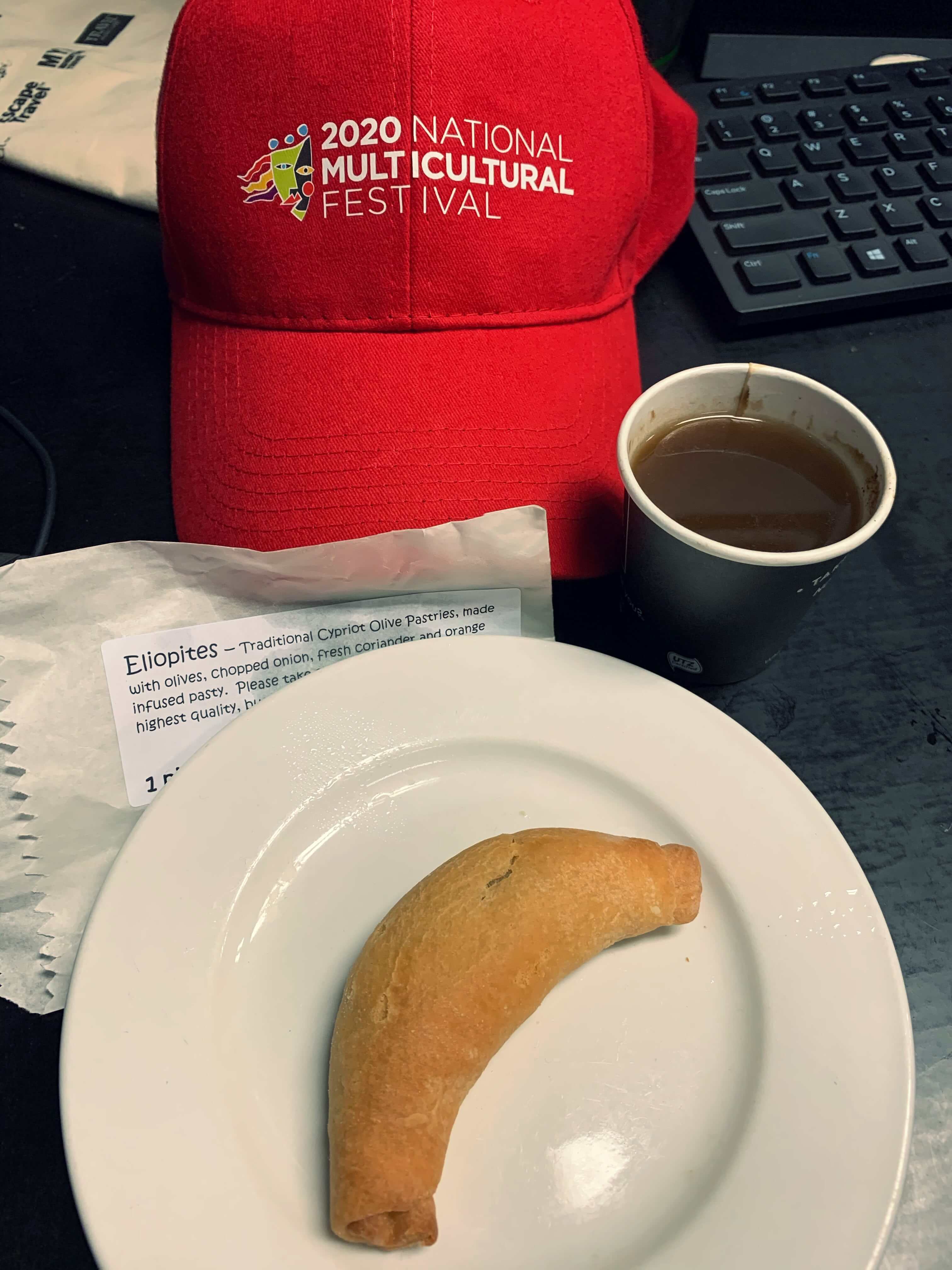

The section I stood at featured the Greek community and culture. From Zorba dance and olive pastries to sipping black traditional Greek coffee, I had a wonderful time, nodding to tunes I’ll never get out of my head.

As I waddled over to the Latin American zone, loud maracas and drums invited me with floral t-shirts and unpronounceable words. It was the most warm and welcoming experience I’ve ever had. Charged by my volunteer status, I walked right to the front—not because I was being an arsehole, but because being 5 feet and a couple of inches, in a crowd, I can’t see anything other that people’s sweaty, muscly, arms.

While the groovy Peruvian music troupe sang and danced, the audience had a party of its own. People in all kinds of clothing set their bags on the ground to jump onto the dance floor. It was a perfect amalgamation of traditions—performers came from various Latin American countries and the audience featured black, white, and all shades of the brown in between.

As the festival wound to a close, I’d changed my mind about volunteering. I’d so it all again next year, but now that I know the scale of the event, I’ll be more strategic about channeling my energy and enjoy the event.

After all, what good is volunteering if we don’t have fun?