Please swipe through to view the full gallery. Artwork by Anpu, posted on Facebook.

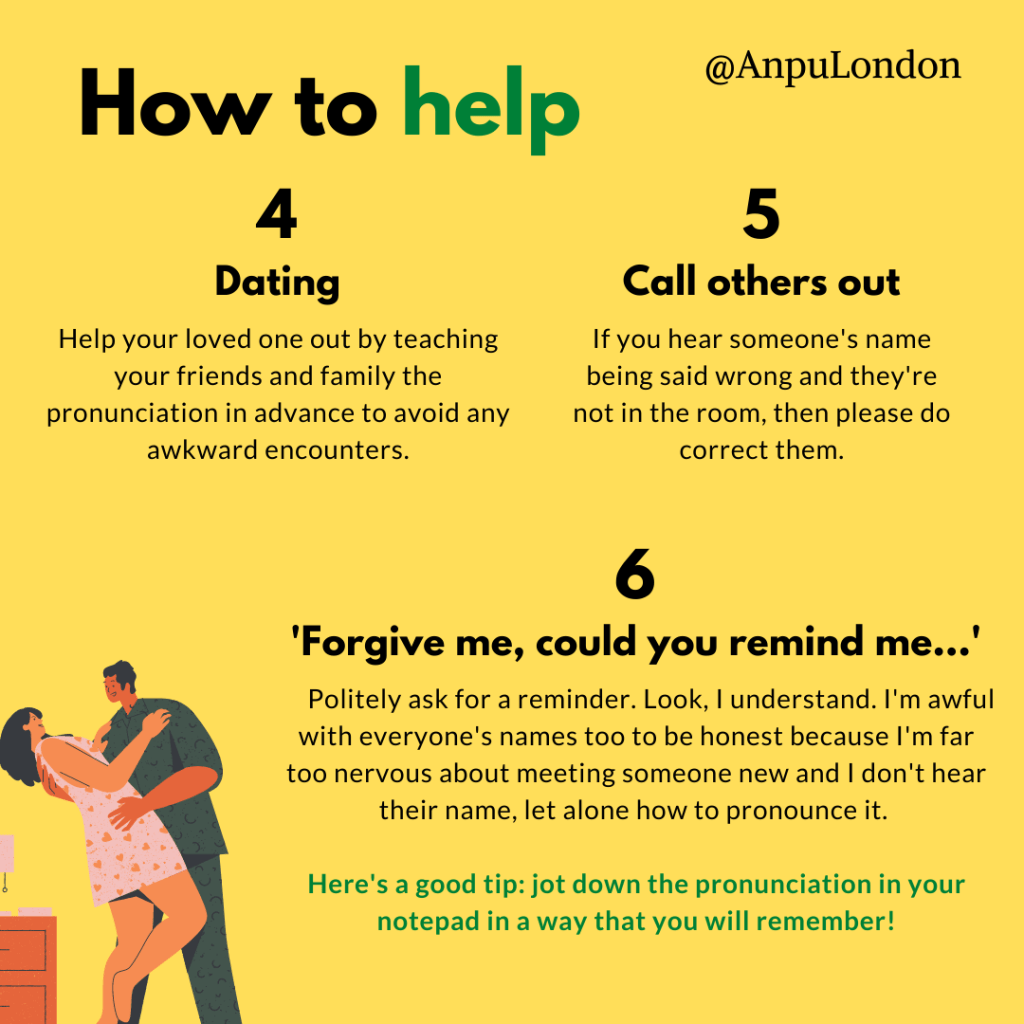

This is fascinating to me. A lot of people in my life do all the right things, according to this artwork. And I appreciate it when people genuinely want to respect me and my ethnic name.

But I don’t care if you get my name wrong because I think we get too attached to names and labels and the cultural baggage that comes with them.

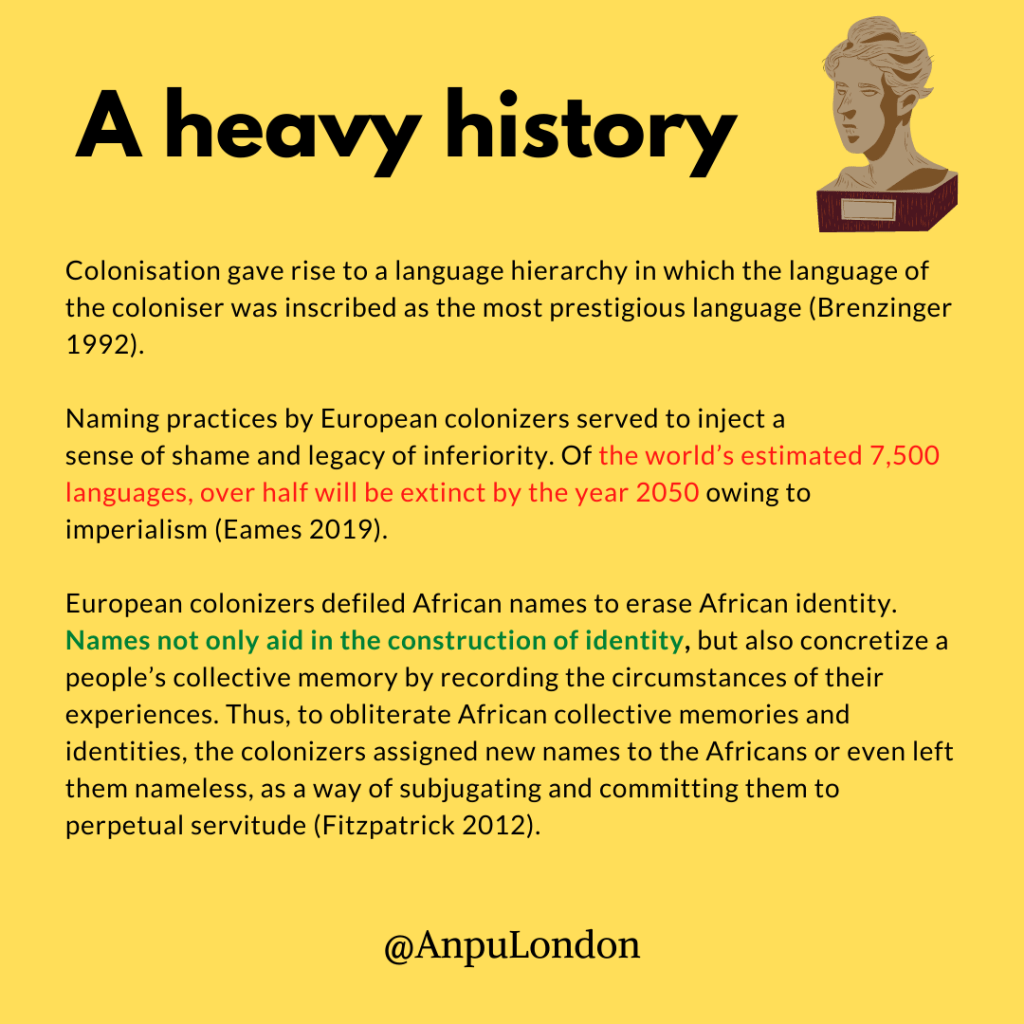

Colonisation created a global hierarchy. So did capitalism. Yes, it’s terrible that the world’s colonial history decimated hundreds of tribes and tribal languages. We should learn from that history. Languages aren’t meant to compete with each other for attention and recognition. Fighting for recognition doesn’t necessarily bring recognition. If we’re to live in one world together, we all need a common language to communicate. That means every one of us will have to make compromises. People like me, who aren’t native English speakers, may have to be ok with English speakers struggling with our names. The same way, English speakers will have to deal with a thick Indian accent if they want their software issues sorted and a rough African accent if they want their parents in aged care looked after. It’s called co-operative existence.

For me, a person is a person. As long as you’re polite and considerate and not racist, you’re fine. If you can’t remember my name, that’s ok. Because guess what, I often get Michael and Matthew mixed up. Beth and Beck are too much alike. By the time we get to Chris, Cris, and Kris, I’m dying. And don’t even get me started on Mick being short for Michael.

If you need an easier way to remember me, just ask. I’d do the same for you. We all take shortcuts sometimes.

Humans named things and each other so we can refer to them in conversation. That’s all. Don’t read too much into it. A name is a name. It’s not your soul. From where I come from, often, a name is a caste. It’s religion. It’s the foundation of hate crimes and human butchery. No one should strut around wielding it like a flag. That’s the kind of devotion that rips countries apart.

Names and labels are just signposts for a dirt road that’ll change and disappear over time. Just because no one will remember a dirt road 50 years from now doesn’t mean the road didn’t exist or serve its purpose. So what if you forget my name? For as long as my being was here and in your life, it’s served its purpose. That’s all we all are—signposts. Sometimes we have letters missing, sometimes we’re scarred or scratched, and some other times we’re just facing the wrong way. Regardless, here and now. If we are, we are.

What’s in a name when a rose by any other name would smell just the same?